How to Write Humor

Melissa and I went out for dinner last night. As we’re enjoying our meal, I told her about my blog posts the last couple of nights, and how they’re part of a limited three-part series. How to Write a Fight Scene and How to Write Dialog were the first two parts.

“What’s the third part?” Melissa asked.

“How to Write Humor.”

“You write humor?”

Comedy, By Way of Change of Status

My introduction is an example of humor through change of a character’s status. In this case, Melissa and I started at roughly equal status, a couple enjoying a meal together. By way of stating I’m writing essays on various aspects of writing, including humor, I’m elevating my status slightly, implying that I’m worthy to write on these subjects.

Melissa’s question at the end drags my status back down. It cuts me off at the knees, and through some alchemy which is completely spoiled by me explaining the joke, we made humor.

This isn’t my favorite approach to comedy, simply because someone has to be the butt of the joke for it to work. It’s punch comedy, and depending on who the victim is, it can punch down.

Howard Taylor did a presentation on this kind of comedy on Writing Excuses Retreat 2018. That’s how I learned about this kind of comedy. Not through Howard making fun of me. It was through his teaching. Howard’s never made of me. He hasn’t. Really.

Comedy, By Way of Absurdity

I like absurdity more than status changes, but it’s harder to pull off. For absurdity to work, the reader’s frame of mind needs to be properly coaxed into the right place so that the absurdity will amuse rather than annoy.

Absurdity is a young man getting into his car on a hot summer day, starting the ignition, and pulling onto the road. He reaches for the A/C controls, flips it to max, and an icy gale funnels out the vents, freezing him into a solid block of ice, still clinging to the steering wheel.

Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett were masters at absurdist comedy. The world building and the tone made for fertile soil for their type of zany to flourish.

Comedy, By Way of Vulgarity

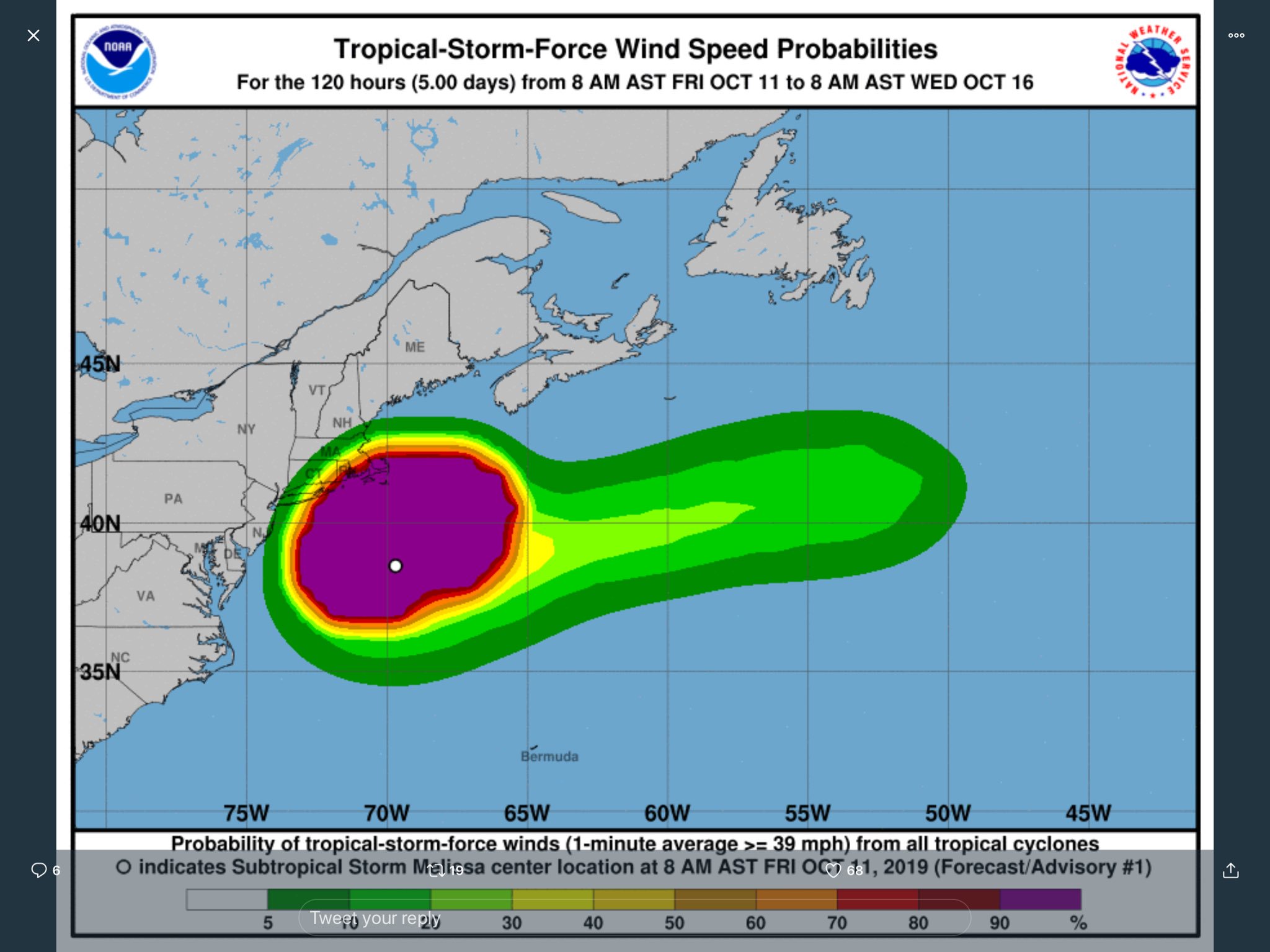

This is tropical storm Melissa.

Melissa is tea-bagging the East Coast. The thrust of this storm is obvious. Melissa is coming in hard and fast, and we have to hope it pulls out before it does too much damage.

That’s comedy by way of vulgarity.

Anything with the power to offend us, such as the profane, also has the power to make us laugh. Poop jokes, fart jokes, jokes about sex… there isn’t much distance between upsetting us and tickling our funny bone.

Ha ha. I said “bone.”

Comedy, By Way of Word Play

Puns and limericks fall into the category of humor via word play. Puns used to be held in much higher regard than they are today. When a good pun lands, it can still make me smile, but they’re not my favorite. I’m not going to punish you all by making you read any lame ones here.

Comedy, By Way of Upsetting Expectations

A man named Joe goes into a bar in New York, situated at the top of a sky scraper. After he gets his drink, another man in a suit sitting next to a window calls out to him.

“Hey buddy, do you know about the wind currents up here?”

“What’s that?” Joe asks.

“As the wind whips between the buildings, it creates a powerful updraft. You can step out right now and the wind is so strong, you won’t even fall.”

“No way!”

“I’ll show you!”

The man in the suit opens the window, steps out, and sure enough, floats in the air.

“I’ve got to try this!” Joe says. He puts down his glass, steps out the window, and promptly plummets to his death.

The man in the suit floats back in the window, picks up Joe’s glass, and takes a drink.

The bartender says, “You know what? You’re a real dick when you’re drunk, Superman.”

Jokes work when they mess with your expectations. There is a surprise at the end, and the surprise has to make sense with everything that came before it. The whole story has to hold together otherwise it has no power to amuse or entertain at all.

This is the kind of humor I like to include in my stories. I like clever twists that change the perspective on everything that came before.

Parting Thoughts

It’s easy to get humor wrong. There are a lot of moving parts to comedy, including timing, delivery, word choice… I’ve only scratched the surface with some high level details, and I’m in too big a hurry tonight to provide more humorous examples.

Jokes are hard. Making something genuinely funny takes a lot of practice and hard work. While some people have a naturally quick wit and good instincts on how to lay out a joke, most of us have to really work at it in order to get the comedy to land.

Your assignment tonight: watch a stand-up comedian. Pay attention to how they deliver the jokes. They usually use all of the things I’ve touched on. Status changes, absurdity, word play… it’s all present in a comedian’s routine. Pay special attention to the way they use planting and payoff in order to subvert and mess with expectations.